Biography

Edited by Bettina Baumgärtel

Angelica Kauffman grows up as an only child and receives an unusually broad education for a girl. Her dual talent for painting and music is encouraged from an early stage by her father Johann Joseph Kauffmann and her mother Cleophea Lutz. Angelica Kauffman has a fine singing voice (soprano) and masters four languages (German, Italian, French and English) at a young age.

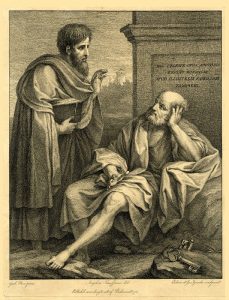

She enjoys success as a portraitist and singer in Austria and Italy while still in her teens (Ill. 12).

Following the early death of her mother in Milan, she decides to make painting her sole career. 40 years later she will thematize the difficulty of this choice in her Self-Portrait Hesitating between the Arts of Music and Painting (Ill. 13).

In 1757 her father is drawn to return to his native Schwarzenberg and she accompanies him on what is her first visit to the Vorarlberg. While he paints the ceiling frescos in the local church, the 15-year-old decorates the side walls with frescos of the thirteen Apostles after G. Piazzetta.

Her second trip to Italy, which lasts from c. 1758/59 to 1766, is devoted wholly to her training as an artist. She works to the point of exhaustion in the famous collections of the Modena d’Este in Milan, the Sampieri in Bologna, the Medici in Florence, the Borghese in Rome and the King of Naples. She studies Old Master works and paints copies for British travellers on the Grand Tour. During this period she establishes important links with English clients that will later serve her well in London (Ill. 14).

It is her ambition right from the outset to succeed in the noblest and most exclusively male genre of them all, history painting. To this end, she builds up networks across Europe and cultivates contacts with travellers on the Grand Tour not just from Britain, but also from France, Russia, Poland and Germany.

Between 1762 and 1779 she produces a total of 41 autograph etchings. She was probably introduced to the technique of etching by her long-standing friend Johann Friedrich Reiffenstein during her stay in Florence.

From 1763 to 1765 she studies classicist art theory in the Eternal City and pursues Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s maxim of “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur”. Her 1764 painting of Winckelmann (Zurich, Kunsthaus), in which she takes up the compositional type of the scholar portrait, signals her breakthrough as a portraitist. In Rome she also produces her first large pictures of mythological subjects, laying the foundations of her career as a history painter.

Arriving in London in 1766, where she will stay until 1781, her name is soon on everyone’s lips. Under the patronage of the Queen Mother, she executes two large-format portraits of female royalty. [Image Gallery] For the English, Scottish and Irish nobility, having a portrait painted by the talented young woman now becomes the done thing.

Having already been elected a member of the Bologna art academy at the age of just 21, and subsequently of the academies in Florence, Rome and Venice, in 1768 she becomes one of the 22 founding members of the Royal Academy headed by Joshua Reynolds. Alongside still-life painter Mary Moser (1744–1819), she will remain the only female Academician for the next 200 years (Ill. 15).

In addition to ground-breaking history paintings, during her time in London she paints numerous graceful scenes based chiefly on antique and literary sources such as Homer, Virgil and Tasso. Small, atmospheric pictures of women abandoned by their lovers, such as Ariadne, Calypso and ‘Poor Maria’ from Laurence Sterne’s bestselling A Sentimental Journey, provide the commercially astute paintress with a lucrative income. With these scenes tinged with delicate feeling, the artist becomes an early proponent of Sensibility and herself becomes the embodiment of the new sentimental female ideal of a ‘beautiful soul’.

In London she is celebrated as a leading representative of classicism amongst an international circle of artists. She achieves fame and wealth, not least due to the reproduction and widespread sale of decorative stipple engravings of her paintings. Many of these engravings, in red or brown ink, are produced by William W. Ryland and Francesco Bartolozzi, both of theme supreme masters of the crayon manner and stipple technique, and are snapped up even in less well-to-do circles.

These prints serve as design templates for many young artists and a fashion for art à la Kauffman sweeps the whole of Europe, contributing enormously to her popularity [Reproductive Prints].

The prestigious commission from the Royal Academy to execute four ceiling paintings for Somerset House (1780, Invention, Composition, Design and Colouring), represents a highpoint in her career [Image Gallery].

In summer 1771 she accepts an invitation to visit Ireland, where she immediately attracts commissions from the country’s leading art collectors.

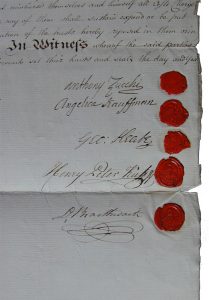

Having being tricked into her first marriage by an imposter at the start of her London period, she only enters into a second marriage at the age of 39. As a safeguard, the marriage contract that she draws up with the Venetian vedutà painter Antonio Zucchi guarantees her the free disposal of her income (Ill. 16).

In 1781 she leaves London with her father and husband in order to settle permanently in her adoptive home, Rome. During their stopover in Venice, her father dies.

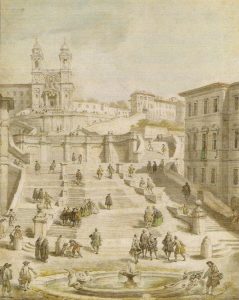

In 1782 Angelica Kauffman opens a prestigious studio beside the Spanish Steps and builds up an international clientele. As in London, Kauffman’s salon becomes a meeting place for the intellectual elite of the 18th century, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottfried Herder. Among her patrons are illustrious members of Europe’s senior aristocracy, including Tsar Paul I of Russia, the kings of Naples and Poland, and the Austrian Emperor Joseph II, high-ranking church dignitaries such as Pope Pius VI, and collectors and intermediaries from the spheres of diplomacy, commerce and banking, such as the French ambassador to the Vatican, François Pierre de Bernis, and his British counterpart, the diplomat and cicerone Thomas Jenkins (Ill. 17).

Kauffman cultivates friendships with leading figures in the world of science, literature and the arts, including with the poets Salomon Gessner and Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, the geologist Déodet de Dolomieu, the physician Auguste Tissot, the poetesses Friederike Brun [Reception] and Fortunata Sulgher Fantastici and fellow women painters such as Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (Ill. 18, 19).

In 1784 she completes her largest portrait painting, the Royal Family of Naples, on behalf of Ferdinand IV and his wife Queen Maria Carolina of Austria. The latter presses her in vain to accept an appointment as court painter [Image Gallery].

Years before the outbreak of the French Revolution, Kauffman paints a number of large-format history paintings illustrating the civic virtues of the Roman Republic. She regularly gives centre stage to female figures from history and literature, such as Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi [Image Gallery], whom she presents as new heroines. She thus helps shape the new ideal of womanhood in the Enlightenment.

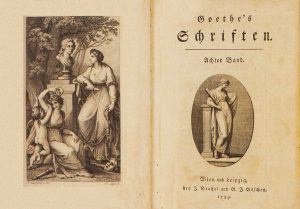

In 1787 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe comes to Rome. He and Kauffman become close friends, but not lovers. Goethe is followed by Anna Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach accompanied by Johann Gottfried Herder [Reception]. Kauffman paints portraits of all three and is soon part of Goethe’s innermost circle (Ill. 20).

In 1788 her husband’s brother, engraver Giuseppe Carlo Zucchi, publishes the first part of a biography of his celebrated sister-in-law, ensuring her posthumous fame even during her own lifetime.

When French troops occupy Rome in 1798, although Kauffman’s studio is spared from looting, her finances are adversely affected by devaluation.

In 1802 she visits Como for her health (Ill. 21).

In 1805 she completes one last large-scale portrait commission for Crown Prince Ludwig I of Bavaria (Munich, Neue Pinakothek). Religious subjects gain the upper hand in her late work.

Upon her death on 5 November 1807 at the age of 66, the artist leaves behind a prolific oeuvre of over 800 works, a rich collection of art and books, and a large fortune. Over 1000 engravings based on her originals, countless copies, works by followers, forgeries, and a flood of publications on her life and work testify to her popularity, which continues unabated right up to today.

Her funeral in the church of S. Andrea delle Fratte in Rome is the grandest since that of the great Raphael. Her coffin is carried by professors from the Academy, including her friend Antonio Canova, and is escorted by her last history paintings and a huge cortège.

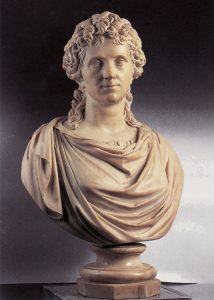

Her bust, made by her cousin Johann Peter Kaufmann, is placed inside the Pantheon alongside that of Raphael (Ill. 22).

As a woman artist in the 18th century, Angelica Kauffman faced an arduous path of emancipation. Even if she advanced not with aggressive means but with quiet tenacity and shrewd strategy, she is undoubtedly a pioneering figure for professional woman artists even today.

Despite her astonishing career path as a female artist who combined her character as a cosmopolitan, educated European woman with her business acumen in a male world, Angelica Kauffman felt a bond with her father’s native village all her life. In her will as during her lifetime, the deeply religious artist gave generously to the Kauffman family, whose branches extended as far as Lucerne, and made provision for the creation of a charitable foundation.

Citation note:

Baumgärtel, Bettina: Angelica Kauffman – Biography, in: Angelika Kauffmann Research Project – online, https://www.angelika-kauffmann.de/en/biography/ [add date of access here]